Thursday, November 29, 2007

Monday, November 19, 2007

Plato

Plato was born in Athens in 427 B.C. He was “the son of wealthy and influential Athenian parents” named Ariston and Perictione. Plato had two brothers named Adeimantus and Glaucon, as well as a younger sister named Potone. Ariston died when Plato was young. When his mother remarried, Plato found himself with a new stepbrother named Antiphon. (source)

“Plato enjoyed success in athletics and engaged in both poetry and drama.” (source) “An aristocratic man with plenty of money and a superb physique, Plato at one time won two prizes as a championship wrestler. Actually, the man’s real (and little known) name was Aristocles; Plato was just a nickname given to him by his friends, whose original connotation made reference to his broad shoulders.” (Morris 326)

However, his sort of lifestyle changed when, “around 409 B.C., Plato met Socrates and became his devoted follower.” (source) This is interesting because his uncle, Charmides, was one of Socrates’ close friends.

Socrates engaged Plato in serious questions about life such as, “What are virtue, wisdom, courage, beauty, piety, bravery, justice?” Since Socrates wrote none of his thoughts down, we must rely on Plato’s records of his dialogues.

“Following the end of the Peloponnesian war, an oligarchic tyranny called the ‘Thirty Tyrants’ ruled Athens for eight months from 404-403 B.C…[Plato’s] uncles, Critias and Charmides, belonged to the Thirty Tyrants and invited their nephew to join them. The junta was dissolved through civil war before Plato could decide.” (source)

Socrates was arrested later for undermining the religion of Athens and for “corrupting the youth.” (Video) Plato recorded Socrates’ speeches at his trial in Apology. Plato was there to witness Socrates' death of drinking a cup of hemlock in 399 B.C.

“When the master died, Plato travelled to Egypt and Italy, studied with students of Pythagoras, and spent several years advising the ruling family of Syracuse. Eventually, he returned to Athens and established his own school of philosophy at the Academy.” (source) (Craig 794)

“Socrates taught Plato, Plato taught Aristotle, Aristotle taught Alexander the Great.” (source)

“Subjects taught in the University included astronomy, biological sciences, mathematics, and political science. According to legend, his University stood in a place that was once owned by the Greek hero, Academus. That's where we began to use the term ‘academy’ when referring to schools.” (source) “For students enrolled there, Plato tried both to pass on the heritage of a Socratic style of thinking and to guide their progress through mathematical learning to the achievement of abstract philosophical truth.” (source)

Plato spent the rest of his life in charge of and teaching in his academy. He died in 347 B.C. “His end was peaceful and happy, for he is supposedly to have died in his sleep at the age of eighty after having attended the wedding feast of one of his students.” (source) (source)

Works Cited

Craig, Edward. The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York: Routledge. 2005.

Morris, Tom. Philosophy for Dummies. Foster City, CA: IDG Books Worldwide, Inc. 1999.

Video on Greece we watched in class

Plato (on the left) walking with Aristotle

“Plato enjoyed success in athletics and engaged in both poetry and drama.” (source) “An aristocratic man with plenty of money and a superb physique, Plato at one time won two prizes as a championship wrestler. Actually, the man’s real (and little known) name was Aristocles; Plato was just a nickname given to him by his friends, whose original connotation made reference to his broad shoulders.” (Morris 326)

However, his sort of lifestyle changed when, “around 409 B.C., Plato met Socrates and became his devoted follower.” (source) This is interesting because his uncle, Charmides, was one of Socrates’ close friends.

Socrates engaged Plato in serious questions about life such as, “What are virtue, wisdom, courage, beauty, piety, bravery, justice?” Since Socrates wrote none of his thoughts down, we must rely on Plato’s records of his dialogues.

“Following the end of the Peloponnesian war, an oligarchic tyranny called the ‘Thirty Tyrants’ ruled Athens for eight months from 404-403 B.C…[Plato’s] uncles, Critias and Charmides, belonged to the Thirty Tyrants and invited their nephew to join them. The junta was dissolved through civil war before Plato could decide.” (source)

Socrates was arrested later for undermining the religion of Athens and for “corrupting the youth.” (Video) Plato recorded Socrates’ speeches at his trial in Apology. Plato was there to witness Socrates' death of drinking a cup of hemlock in 399 B.C.

“When the master died, Plato travelled to Egypt and Italy, studied with students of Pythagoras, and spent several years advising the ruling family of Syracuse. Eventually, he returned to Athens and established his own school of philosophy at the Academy.” (source) (Craig 794)

“Socrates taught Plato, Plato taught Aristotle, Aristotle taught Alexander the Great.” (source)

“Subjects taught in the University included astronomy, biological sciences, mathematics, and political science. According to legend, his University stood in a place that was once owned by the Greek hero, Academus. That's where we began to use the term ‘academy’ when referring to schools.” (source) “For students enrolled there, Plato tried both to pass on the heritage of a Socratic style of thinking and to guide their progress through mathematical learning to the achievement of abstract philosophical truth.” (source)

Plato spent the rest of his life in charge of and teaching in his academy. He died in 347 B.C. “His end was peaceful and happy, for he is supposedly to have died in his sleep at the age of eighty after having attended the wedding feast of one of his students.” (source) (source)

Works Cited

Craig, Edward. The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York: Routledge. 2005.

Morris, Tom. Philosophy for Dummies. Foster City, CA: IDG Books Worldwide, Inc. 1999.

Video on Greece we watched in class

Plato (on the left) walking with Aristotle

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Socrates

In the year of 470 B.C., Socrates was born in Athens to a stone-carver and a mid-wife. He also worked with stone, but was never as good as his father. He fought for his home city in the Peloponnesian War when he was older. (source, Schofield 63)

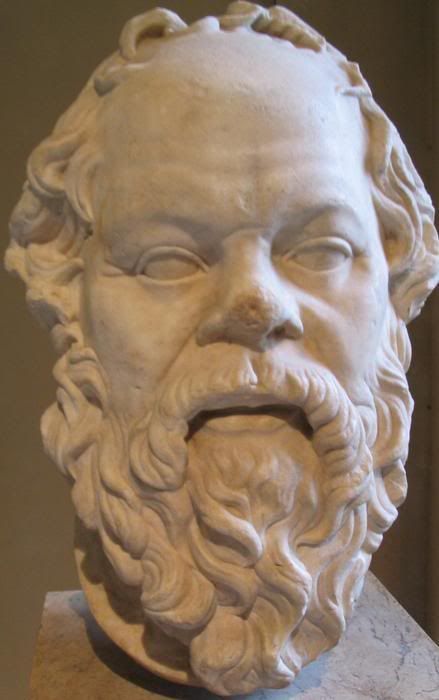

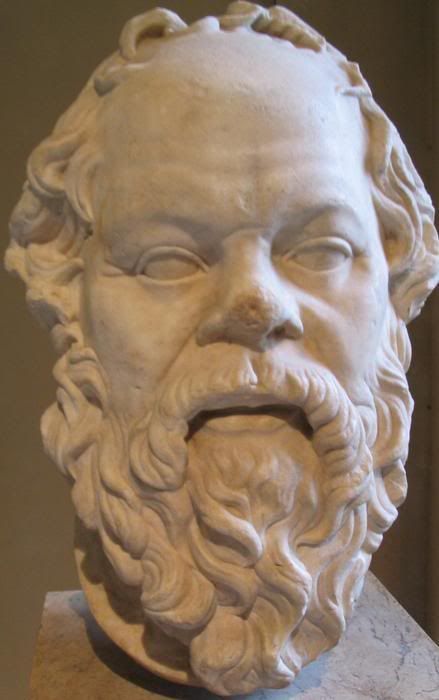

“Socrates was ugly, potbellied, had bulging eyes and a snub nose.” (source) He apparently didn’t care about his appearance or what others thought of it.

It wasn’t until he was in his forties when he began to ask serious questions about life, such as “What are virtue, wisdom, courage, beauty, piety, bravery, justice?” Some of his famous statements were “The unexamined life is not worth living” (source) and “know thyself.”

We still study Socrates’ philosophy today, examining it, agreeing and disagreeing. Some of the things that he believed we still believe today, such as having a conscience. Also, “Socrates believed in the existence of gods vastly superior to ourselves in wisdom and power.” (source) Although Christians are not polytheistic, we do believe in one God “vastly superior to ourselves in wisdom and power.” (source) (source1, source2)

Socrates introduced a way to “teach” that some still use today, called the Socratic Method. This is a “method of teaching in which the master imparts no information but asks a sequence of questions, through answering which the pupil eventually comes to the desired knowledge.” (philosophyuncc) “Socrates taught Plato, Plato taught Aristotle, Aristotle taught Alexander the Great.” (source)

Socrates didn’t write any of his thoughts down, so we have to rely on Plato’s writings of his dialogues. “Socrates believed in the superiority of argument over writing and spent the greater part of his life in the marketplace and public places of Athens. He engaged in dialogue and argument with anyone who would listen or who would submit to interrogation.” (source)

“At about fifty he married Xanthippe and had three children.” (source) Xanthippe “had a bad temper and was the worst kind of a grouch. She thought Socrates was wasting his time, that he was a loafer, as he did no work that brought in any money. One day she scolded him so loudly that he left the house, whereupon she threw a bucket of water on him. Socrates, who never answered back, merely remarked to himself: ‘After thunder, rain may be expected.’” (Hillyer 172)

However, this great philosopher’s calm life would soon change drastically. When Athens fell, Athens needed a scapegoat. They couldn’t blame the gods, so they turned to blame someone “unfaithful.” Socrates seemed like the obvious choice. (Video)

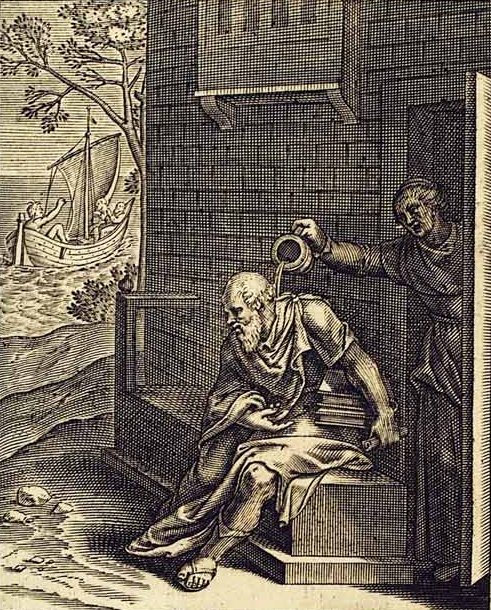

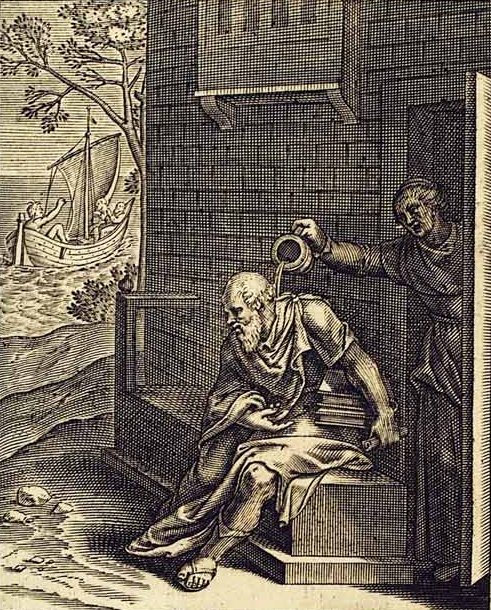

Socrates was arrested for undermining the religion of Athens and for “corrupting the youth.” (Video) When he stood up to speak, he did not apologize or plea for mercy. Rather, he said that Athens owed him something. This was not a good way to gain favor in the eyes of the 500 men in the jury. “Socrates was found guilty and sentenced to death by drinking a cup of hemlock. He turned down the pleas of his disciples to attempt an escape from prison, which had apparently been planned and only required Socrates’ willingness to escape. He did not want to. Socrates stated that he would have to flee from Athens. Having knowingly agreed to live under the city’s laws, he subjected himself to the possibility of being accused of crimes by its citizens and judged guilty by its jury. To do otherwise would cause him to break his ‘contract’ with the state, and by so doing, he felt he was harming it, which was something that went against his principles. As such, he preferred to drink the hemlock. According to Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates died [in 399 B.C.] in the company of his friends and had a calm death, enduring his sentence with fortitude.” (source)

“Soon after his death his accusers were turned upon and the state, realising their mistake, erected a statue to him.” (source)

Works Cited

Hillyer, Virgil M. A Child’s History of the World. Hunt Valley, Maryland: Calvert Education Services. 1997.

Schofield, Louise. Ancient Greece. San Francisco: Fog City Press. 2005.

Video on Greece we watched in class

“Socrates was ugly, potbellied, had bulging eyes and a snub nose.” (source) He apparently didn’t care about his appearance or what others thought of it.

It wasn’t until he was in his forties when he began to ask serious questions about life, such as “What are virtue, wisdom, courage, beauty, piety, bravery, justice?” Some of his famous statements were “The unexamined life is not worth living” (source) and “know thyself.”

We still study Socrates’ philosophy today, examining it, agreeing and disagreeing. Some of the things that he believed we still believe today, such as having a conscience. Also, “Socrates believed in the existence of gods vastly superior to ourselves in wisdom and power.” (source) Although Christians are not polytheistic, we do believe in one God “vastly superior to ourselves in wisdom and power.” (source) (source1, source2)

Socrates introduced a way to “teach” that some still use today, called the Socratic Method. This is a “method of teaching in which the master imparts no information but asks a sequence of questions, through answering which the pupil eventually comes to the desired knowledge.” (philosophyuncc) “Socrates taught Plato, Plato taught Aristotle, Aristotle taught Alexander the Great.” (source)

Socrates didn’t write any of his thoughts down, so we have to rely on Plato’s writings of his dialogues. “Socrates believed in the superiority of argument over writing and spent the greater part of his life in the marketplace and public places of Athens. He engaged in dialogue and argument with anyone who would listen or who would submit to interrogation.” (source)

“At about fifty he married Xanthippe and had three children.” (source) Xanthippe “had a bad temper and was the worst kind of a grouch. She thought Socrates was wasting his time, that he was a loafer, as he did no work that brought in any money. One day she scolded him so loudly that he left the house, whereupon she threw a bucket of water on him. Socrates, who never answered back, merely remarked to himself: ‘After thunder, rain may be expected.’” (Hillyer 172)

However, this great philosopher’s calm life would soon change drastically. When Athens fell, Athens needed a scapegoat. They couldn’t blame the gods, so they turned to blame someone “unfaithful.” Socrates seemed like the obvious choice. (Video)

Socrates was arrested for undermining the religion of Athens and for “corrupting the youth.” (Video) When he stood up to speak, he did not apologize or plea for mercy. Rather, he said that Athens owed him something. This was not a good way to gain favor in the eyes of the 500 men in the jury. “Socrates was found guilty and sentenced to death by drinking a cup of hemlock. He turned down the pleas of his disciples to attempt an escape from prison, which had apparently been planned and only required Socrates’ willingness to escape. He did not want to. Socrates stated that he would have to flee from Athens. Having knowingly agreed to live under the city’s laws, he subjected himself to the possibility of being accused of crimes by its citizens and judged guilty by its jury. To do otherwise would cause him to break his ‘contract’ with the state, and by so doing, he felt he was harming it, which was something that went against his principles. As such, he preferred to drink the hemlock. According to Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates died [in 399 B.C.] in the company of his friends and had a calm death, enduring his sentence with fortitude.” (source)

“Soon after his death his accusers were turned upon and the state, realising their mistake, erected a statue to him.” (source)

Works Cited

Hillyer, Virgil M. A Child’s History of the World. Hunt Valley, Maryland: Calvert Education Services. 1997.

Schofield, Louise. Ancient Greece. San Francisco: Fog City Press. 2005.

Video on Greece we watched in class

Saturday, November 10, 2007

Plato's Meno

“Socrates (c.470-c.399 B.C.) [was] an Athenian philosopher. He taught his students by questions and answers and encouraged them to discuss weaknesses in the government and people’s beliefs.” (Schofield 63) Some believe that Socrates was the first person in history to know how to make a well-thought-out argument against a thought. (C.D.)

“The problem of reconstructing the life of Socrates has been compared to that of writing the life of Christ. Neither wrote a word of his teachings, which have been preserved, not always consistently, in the writings of their disciples.” (Cartledge 125) However, Plato (Socrates’s student) wrote down some of his works for him.

The work starts when Meno asks how virtue is acquired. Socrates doesn’t know what virtue is, so Meno tells him that there are different kinds of virtues for different people.

Socrates then comes in from a new angle:

Meno then tries to define virtue a bit differently.

Socrates then goes on to ask again if Meno said that justice and temperance and the like were virtues, and he agrees, but Socrates wants a whole.

Meno later asks how we can enquire and how we know that the answer is the right one, but Socrates dismisses the question as tiresome. Socrates then says that we cannot learn, but only recall things that we already know. He demonstrates on a little boy by only asking him questions and making sure by Meno that no one else taught him those things.

Socrates says that we should enquire because we are “better and braver and less helpless if we think that we ought to enquire, than we should have been if we indulged in the idle fancy that there was no knowing and no use in seeking to know what we do not know.” (source)

Socrates asks, “wisdom is inferred to be that which profits-and virtue, as we say, is profitable? Men. Certainly. Soc. And thus we arrive at the conclusion that virtue is either wholly or partly wisdom? Men. I think that what you are saying, Socrates, is very true.” (source) Socrates comes to the conclusion that virtue is wisdom and must be taught. But he later discards it because there are no teachers, disciples, or scholars of virtue. He proves this by asking Anytus, a wise and smart aristocrat.

Socrates also says that a right opinion should be placed equal to knowledge. I personally would disagree with this because knowledge is factual. An opinion is just something that one thinks is true. If an opinion was factual, it would be knowledge, not an opinion.

Socrates concludes that virtue is not taught nor given to man by nature, so it must be God-given. This is ironic because he was later put to death for not believing in the gods, as well as “treason and corruption of the young.” (source) (source)

Works Cited

Cartledge, Paul. The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization. New York: T.V. Books, L.L.C. 2000.

C.D. we listened to in class

Schofield, Louise. Ancient Greece. San Francisco: Fog City Press. 2005.

On the left: Plato, on the right: Meno

On the left: Socrates, on the right: Atryum

“The problem of reconstructing the life of Socrates has been compared to that of writing the life of Christ. Neither wrote a word of his teachings, which have been preserved, not always consistently, in the writings of their disciples.” (Cartledge 125) However, Plato (Socrates’s student) wrote down some of his works for him.

The work starts when Meno asks how virtue is acquired. Socrates doesn’t know what virtue is, so Meno tells him that there are different kinds of virtues for different people.

“There will be no difficulty, Socrates, in answering your question. Let us take first the virtue of a man-he should know how to administer the state, and in the administration of it to benefit his friends and harm his enemies; and he must also be careful not to suffer harm himself. A woman's virtue, if you wish to know about that, may also be easily described: her duty is to order her house, and keep what is indoors, and obey her husband. Every age, every condition of life, young or old, male or female, bond or free, has a different virtue: there are virtues numberless, and no lack of definitions of them; for virtue is relative to the actions and ages of each of us in all that we do. And the same may be said of vice, Socrates.” (source)Socrates proves that virtue is the same for all people and argues that it should be defined as a whole, not having different things like courage and temperance being defined as virtues.

Socrates then comes in from a new angle:

“Well, I will try and explain to you what figure is. What do you say to this answer?-Figure is the only thing which always follows colour. Will you be satisfied with it, as I am sure that I should be, if you would let me have a similar definition of virtue?”(source) “Men. If you want to have one definition of them all, I know not what to say, but that virtue is the power of governing mankind.” (source) “Yet once more, fair friend; according to you, virtue is "the power of governing"; but do you not add "justly and not unjustly"? Men. Yes, Socrates; I agree there; for justice is virtue. Soc. Would you say "virtue," Meno, or "a virtue"? Men. What do you mean? Soc. I mean as I might say about anything; that a round, for example, is "a figure" and not simply "figure," and I should adopt this mode of speaking, because there are other figures. Men. Quite right; and that is just what I am saying about virtue-that there are other virtues as well as justice. Soc. What are they? tell me the names of them, as I would tell you the names of the other figures if you asked me. Men. Courage and temperance and wisdom and magnanimity are virtues; and there are many others. Soc. Yes, Meno; and again we are in the same case: in searching after one virtue we have found many, though not in the same way as before; but we have been unable to find the common virtue which runs through them all.” (source)Socrates later brings the topic around to another point when he says,

“Is it not obvious that those who are ignorant of their [evil] nature do not desire them; but they desire what they suppose to be goods although they are really evils; and if they are mistaken and suppose the evils to be good they really desire goods?” (source)I personally disagree with this quote because one can be doing something that they don’t know is wrong, but if they did know, would still do it anyway. In other words, one can be doing something that they don’t know is evil, but they still desire that evil thing that they are doing. Just because one is ignorant doesn’t mean one is perfect.

Meno then tries to define virtue a bit differently.

“Virtue is the desire of things honourable and the power of attaining them.” (source) “Soc. But if this be affirmed, then the desire of good is common to all, and one man is no better than another in that respect? Men. True. Soc. And if one man is not better than another in desiring good, he must be better in the power of attaining it? Men. Exactly. Soc. Then, according to your definition, virtue would appear to be the power of attaining good? Men. I entirely approve, Socrates, of the manner in which you now view this matter. Soc. Then let us see whether what you say is true from another point of view; for very likely you may be right:-You affirm virtue to be the power of attaining goods? Men. Yes. Soc. And the goods which mean are such as health and wealth and the possession of gold and silver, and having office and honour in the state-those are what you would call goods? Men. Yes, I should include all those. Soc. Then, according to Meno, who is the hereditary friend of the great king, virtue is the power of getting silver and gold; and would you add that they must be gained piously, justly, or do you deem this to be of no consequence? And is any mode of acquisition, even if unjust and dishonest, equally to be deemed virtue? Men. Not virtue, Socrates, but vice. Soc. Then justice or temperance or holiness, or some other part of virtue, as would appear, must accompany the acquisition, and without them the mere acquisition of good will not be virtue. Men. Why, how can there be virtue without these? Soc. And the non-acquisition of gold and silver in a dishonest manner for oneself or another, or in other words the want of them, may be equally virtue? Men. True. Soc. Then the acquisition of such goods is no more virtue than the non-acquisition and want of them, but whatever is accompanied by justice or honesty is virtue, and whatever is devoid of justice is vice. Men. It cannot be otherwise, in my judgment.” (source)

Socrates then goes on to ask again if Meno said that justice and temperance and the like were virtues, and he agrees, but Socrates wants a whole.

Meno later asks how we can enquire and how we know that the answer is the right one, but Socrates dismisses the question as tiresome. Socrates then says that we cannot learn, but only recall things that we already know. He demonstrates on a little boy by only asking him questions and making sure by Meno that no one else taught him those things.

Socrates says that we should enquire because we are “better and braver and less helpless if we think that we ought to enquire, than we should have been if we indulged in the idle fancy that there was no knowing and no use in seeking to know what we do not know.” (source)

Socrates asks, “wisdom is inferred to be that which profits-and virtue, as we say, is profitable? Men. Certainly. Soc. And thus we arrive at the conclusion that virtue is either wholly or partly wisdom? Men. I think that what you are saying, Socrates, is very true.” (source) Socrates comes to the conclusion that virtue is wisdom and must be taught. But he later discards it because there are no teachers, disciples, or scholars of virtue. He proves this by asking Anytus, a wise and smart aristocrat.

Socrates also says that a right opinion should be placed equal to knowledge. I personally would disagree with this because knowledge is factual. An opinion is just something that one thinks is true. If an opinion was factual, it would be knowledge, not an opinion.

Socrates concludes that virtue is not taught nor given to man by nature, so it must be God-given. This is ironic because he was later put to death for not believing in the gods, as well as “treason and corruption of the young.” (source) (source)

Works Cited

Cartledge, Paul. The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization. New York: T.V. Books, L.L.C. 2000.

C.D. we listened to in class

Schofield, Louise. Ancient Greece. San Francisco: Fog City Press. 2005.

On the left: Plato, on the right: Meno

On the left: Socrates, on the right: Atryum

Saturday, November 3, 2007

Greek Architecture

Athens had lots of new ideas coming into it because it was the center of trade during its time. “If New York City is ‘The Big Apple,’ Athens was ‘The Big Olive.’” (Video) Everyone came to them and it even started to turn into a polyglot society. However, “while absorbing what the near east had to offer…[such as architecture and religion,] the Greeks continued to make everything they took over into something astonishingly different-and original.” (Grant 11) We can see this when we look at their architecture.

“In ancient Greece, poor people and rich people lived in different kinds of houses. All houses were made of mud bricks and needed frequent repairs. Houses of the poor people were very simple compared to the houses of the rich, which had more rooms centered around a courtyard…The floors and walls in the houses were carefully created using stones, tiles, or pebbles. The nicest houses used pebbles to create mosaics. To do this, they went to the seashore and collected colored pebbles of similar sizes and arranged them in sand to make a picture or pattern on the floors or walls.”

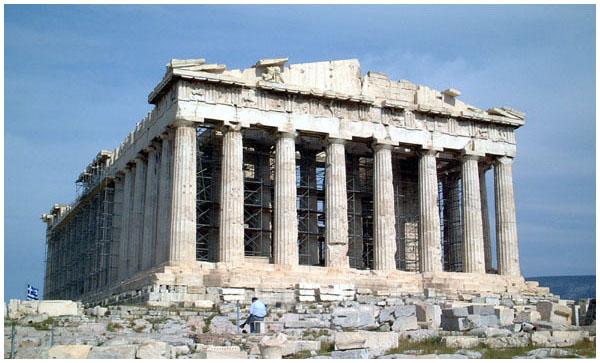

Perhaps the most amazing parts of ancient Greek architecture were their large and gorgeous temples. We must rely on their temples for most of our information since they are one of the only surviving buildings from that time. The first stone temples appeared in large numbers during the 8th century B.C. and the 7th century B.C. “These temples were often only big enough to house a cult statue and were not meant to be places for large gatherings of people. A typical Greek temple had a long, inner chamber surrounded by columns.” “The Greek marble temples, for example, are known to have displayed blue, green, red and gold colors. The color is thought to have enhanced the optical experience of the building and to highlight the architectural sculpture.” “Beneath the temples spread public meeting places, civic buildings, gymnasiums, stadiums, theaters, and housing.” Though not much remains of these temples, we can imagine the glory they had at their peak. (source1, source2)

The three kinds of columns used by the Greeks to build these splendors and to hold up the roofs were Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

“The Doric order is plain and sturdy looking. It was developed by the Dorian tribes on the Greek mainland who were heavily influenced by buildings at Mycenae and Crete. The greatest example of Doric order is the Parthenon which was built around 440.”

“The Ionic order originated along the coast of the Asia Minor. The Ionic column is taller and more slender than the Doric. Unlike the Doric, the Ionic column has a base. The most distinctive feature of the ionic column is the scroll shape of the capitol, which made it slightly fancier than the Doric. The Ionic order was more popular in the eastern parts of Greece where there was an emphasis on elegance and ornamentation.”

“The Corinthian order was built to be sturdier than the Ionic order. It was also more decorative with elaborate leaf designs at the top of the columns. This was the style that most influenced Roman architecture” even though it wasn’t used that much in Greece.

“Some things today can be traced back to the ancient Greeks [as we have already

seen,] such as theatre.” (Malam 5) The Greeks are well known for their amphitheaters. These were semi-circles “with rising tiers of seats [which look like steps] about an open space called the arena” where the orchestra would play and the actors would perform using masks to show happiness or sadness.

seen,] such as theatre.” (Malam 5) The Greeks are well known for their amphitheaters. These were semi-circles “with rising tiers of seats [which look like steps] about an open space called the arena” where the orchestra would play and the actors would perform using masks to show happiness or sadness.Many years later, one can look around and still see some of ancient Greece. “Classic Greek architecture is reflected on modern day buildings such as the Lincoln Memorial…The Lincoln Memorial uses the Doric order.” A bigger example would be the White House.

“The White House is a grand mansion…with details that echo classical Greek Ionic architecture.

“The White House is a grand mansion…with details that echo classical Greek Ionic architecture.  James Hoban's original design was modeled after the Leinster House in Dublin, Ireland.” Thus we see that Greek architecture not only influenced America, but other countries as well.

James Hoban's original design was modeled after the Leinster House in Dublin, Ireland.” Thus we see that Greek architecture not only influenced America, but other countries as well. Works Cited

Grant, Michael. The Founders of the Western World: A History of Greece and Rome. New York: Maxwell Macmillan Publishing Company. 1991.

Malam, John. Ancient Greece. New York: Enchanted Lion Books. 2004.

Video of Greece we watched in class

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)