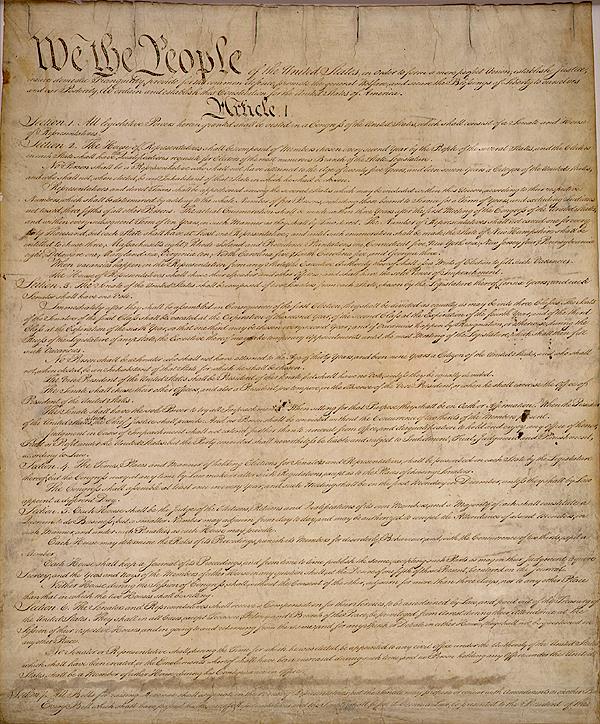

“The document conceded by John and set with his seal in 1215, however, was not what we know today as 'Magna Carta,' but rather a set of baronial stipulations, now lost, known as the ‘Articles of the Barons.’ After John and his barons agreed on the final provisions and additional wording changes, they issued a formal version on June 19, and it is this document that came to be known as 'Magna Carta.' Of great significance to future generations was a minor wording change, the replacement of the term ‘any baron’ with ‘any freeman,’ in stipulating to whom the provisions applied. Over time, it would help justify the application of the Charter's provisions to a greater part of the population. While freemen were a minority in 13th-century England, the term would eventually include all English, just as ‘We the People’ would come to apply to all Americans in this century.” (source)

The document also contained “63 clauses promising all freemen access to courts and a fair trial, eliminating unfair fines and punishments, giving power to the Catholic Church in England, and addressing many lesser issues.” (source) These lesser issues included settling conflicts “between church and monarchy, between individual and the state, between husband and wife, between Jew and Christian, between king and baron, between merchant and consumer, [and] between commoner and privatizer…. Its chapter 39 has grown to embody fundamental principles, habeas corpus, trial by jury, [and] prohibition of torture.” (Linebaugh 45)

The last few sections of the charter “deal with how the Magna Carta would be enforced in England. Twenty-five barons were given the responsibility of making sure the king carried out what was stated in the Magna Carta - the document clearly states that they could use force if they felt it was necessary. [Again,] to give the Magna Carta an impact, the royal seal of King John was put on it to show people that it had his royal support.” (source)

The Magna Carta has been a great influence to Americans, too. “Before penning the Declaration of Independence--the first of the American charters of freedom--in 1776, the Founding Fathers searched for a historical precedent for asserting their rightful liberties from King George III and the English Parliament. They found it in a gathering that took place 561 years earlier on the plains of Runnymede, not far from where Windsor Castle stands today…[the] Magna Carta--a momentous achievement for the English barons and, nearly six centuries later, an inspiration for angry American colonists.” (source) The common American people have looked to this agreement for help, too. A man named Roger B. Taney cited the Magna Carta in an American court 16 times! (Linebaugh 172, 173)

Indeed, the Magna Carta served as a reference point of law for the people of England to go back to if they thought the king was being unfair. This is what America’s Founding Fathers did when they wrote the Declaration of Independence. The charter can be compared to the Constitution, too, in some ways, in that it spelled out the rights of the people. All in all, the Magna Carta, (Latin for “Great Charter,”) was an outstanding document that changed the world and the way it thought about freedom. (Howard 25)

Works Cited

Howard, A. E. Dick. Magna Carta: Text and Commentary. U.S.A.: The University Press of Virginia. 1964.

Linebaugh, Peter. The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. 2008.

The Magna Carta

The Declaration of Independence

The Constitution

1 comment:

5,5,5

Post a Comment